|

FINDINGS

OF AN INTERNAL INVESTIGATION REGARDING THE

DISTRICT’S 2008 SUMMER YOUTH PROGRAM

August

12, 2008

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

In a letter dated July 30, 2008, Mayor Adrian

M Fenty made a request to the District’s Chief Financial Officer to use

the District’s Contingency Cash Reserve Fund to increase the budget

allocated to the city’s Summer Youth Program by $20.1 million, raising

to $52.4 million the projected cost of the program. This increase came

amid concerns that the program was grappling with a number of serious

operational challenges.

This report details these

challenges that led to this increase, their causes, and strategies to

resolving them in 2008 and learning from them in 2009. The major findings

are:

- Approximately $17 million of the Summer Youth

Program’s $37 million budget increase, covered by supplemental

funding and reprogrammings, was the result of a policy decision to

meet increased demand among District youth in need of a summer job or

enrichment program. - The final budget increase of up to $20 million,

however, was the product of significant mismanagement within the

program, which resulted in errors in the program’s payroll system.

Payroll for the fourth pay period will, for the first time since the

program began, pay less than the maximum allowable hours. - There is little confidence in official time and

attendance data because the time entry system contains significant

data errors, which are the consequence of not having complete and

accurate records of where young people are working and how many hours

they have worked in a pay period. Several factors contributed to this

circumstance. The most significant causes are: - A large number of contracts with host organizations

were not awarded until days before the summer program began,

preventing DOES from notifying youth and their parents of their

designated place of work in advance. - Thousands of registration forms were not entered

into the management system early, compounding the impact of

last-minute contract approvals. - The deployment of a new time and attendance system,

which was to be the basis for payroll, less than a week before the

beginning of the program, leaving little time for testing, training,

or identifying problems in the migration of information from the old

system to the new one. - Broken and poorly executed manual work-around

procedures, which prevented DOES from successfully adapting to their

new time entry system’s problems. - Management safeguards failed to raise warnings or call

for outside help. Managers did not adequately challenge assumptions or

demand their verification with data. Statements and explanations were

too often taken at face value. - DOES did not raise concerns along the way. The agency

did not communicate that a breakdown was imminent, minimized problems,

and offered no strategy for effectively resolving the crisis, even

after it developed. - DOES underestimated the depth and complexity of the

data management problems, even after the payroll crisis emerged. The

organization did not have the expertise or adaptability to diagnose

and start to address systematically the problems. - Several allegations involving fraud and abuse have

been confirmed as true, though likely not systemic or pervasive, based

on OCTO’s most recent analysis of payroll and registration records.

This area requires additional investigation. Nevertheless, it is

likely that a significant amount of has been misdirected, lost or

stolen as a consequences of inadequate policy implementation.

Payroll for the fourth pay

period will, for the first time since the program began, pay less than the

maximum allowable hours. The approach is to: 1) identify and remove from

the system people who are not part of the program at this point, and 2)

ensure that payments reflect the program’s most fundamental parameters

involving pay rates, age limits, and allowable hours. OCTO will continue

to methodically gain control of payroll costs, and conduct a profile

analysis to determine if a disproportionate number of problems concentrate

at particular work sites.

To learn from the

experiences of 2008, this report makes the following recommendations:

1.

Invest in programs that work, stop funding those that do

not, based on a rigorous evaluation of program quality and outcomes.

2.

Maintain a

commitment to providing quality experiences to a large number of District

youth.

3.

Reassess the skills required to run the program, and put the

right people in the right job.

4.

Enforce time entry requirements at host organizations, and

penalize those that fail to comply.

5.

Have job assignment available for youth as they register,

with goal of registering a higher percent of participants before the

program begins, by securing contracts earlier or migrating to multi-year

contracts with providers.

6.

Demand that assumptions are relentlessly challenged, and

train DOES staff how to respond to unexpectedly large workflows.

7.

Eliminate all paper processes and bring the entire summer

program online.

8.

Continually validate information to stop fraud and abuse

before or just after it occurs.

9.

Integrate the debit card with the One Card to assist the

city guard against future abuse.

PURPOSE

At the request of Mayor

Adrian Fenty, this report conveys the findings of an internal

investigation of the 2008 Summer Youth Program. Its objectives are to: 1)

identify the problems associated with the program, 2) describe how and why

they developed, and 3) describe actions underway to ensure they do not

happen again.

SCOPE AND METHODOLOGY

To detail the full extent of

problems related to this year’s Summer Youth Program (SYP), we included

in our review events and decisions that date back to the 2007 SYP. We have

also included pertinent information involving the planning process leading

up to the 2008 program. This context is essential in understanding why

problems emerged and why they persisted.

The timeline and data

included in this report continue up until August 11, 2008, or just after

the end of the fourth pay period. Much of the information obtained for

this report came from an examination of data extracts from the program’s

registration system, time and attendance system, and payment system. We

obtained additional information and insights through interviews and

discussions with staff at the following agencies:

·

Department of Employment Services (DOES)

·

Executive Office of the Mayor (EOM)

·

Office of the City Administrator (OCA)

·

Office of Contracting and Procurement (OCP)

·

Office of the Chief Technology Officer (OCTO)

·

Office of the Chief Financial Officer (OCFO)

We also conducted interviews

with individuals at host organizations. It should be noted that the

CapStat team has been reviewing the issues surrounding the SYP throughout

the year. This report reflects that research, conducted over several

months, as well as the work conducted since the Mayor’s request for a

formal investigation was made.

THE FLASH POINT

In a letter dated July 30,

2008, Mayor Adrian Fenty made a request to the District’s Chief

Financial Officer to use the District’s Contingency Cash Reserve Fund to

increase the budget allocated to the city’s Summer Youth Program by

$20.1 million, raising to $52.4 million the projected cost of the program.

This amount represents an increase of more than 250% over the program’s

original budget of $14.5 million.

The urgency of this most

recent request, made at risk of not being able to meet payroll for a

workforce of as many as 21,000 young people, understandably raised a

number of serious questions about the program’s management and

operations. It also brought to the surface allegations of waste, fraud,

and abuse.

How could this happen? How

did it happen? And, how will District government resolve the causes of

these problems? The answers required our research to look back more than a

year.

THE PROGRAM AND THE ORGANIZATION SUPPORTING IT

Each year for nearly 30

years, District government has administered a summer jobs program for

teenagers and young adults, ages 14 – 21, who live in the District.

The size of the program has fluctuated over the years, but its

purpose remains the same: provide jobs and enrichment experiences for

young people who may not otherwise find employment or training during the

summer.

sAt one point, the program

employed more than 20,000 young adults. But by 2003, it reached a low

point in size, employing about 5,500 youth for a six-week period.

Beginning in 2004, the program incrementally, though not consistently,

expanded until 2007, when the city provided jobs, training, and enrichment

experiences for more than 12,629 youth. Even with this near-doubling in

size, there was widespread belief among those interviewed that this did

not go far enough in offering opportunities to out-of-work, out-of-school

teenagers and young adults.

The Department of Employment

Services’s Office of Youth Programs manages the Summer Youth Program,

which is also called the Passport-to-Work Program. This office, composed

of more than 40 FTEs including four managers, is responsible for planning

and implementing the program each year. They also administer a much

smaller year-round job training and employment program.

PROGRAM GOALS FOR 2008

Formal preparations for the

2008 SYP program began in November 2007, and planning for it began even

earlier. The objectives driving these efforts had their roots in lessons

learned from the 2007 program. The 2007 program ran for eight weeks (it

was originally scheduled to run for six, but was extended mid-way through

the program), and begin on June 26. The new leadership at DOES, was able

to incorporate several reforms in time for 2007. Most notably they made a

push to increase enrollment after a year of decline in 2006, extend the

program’s length beyond its original end date, and expand the variety of

summer experiences available to youth.

As early as May 2007, before

the program began, DOES made a list of reforms that they had time to

implement for 2007, and others that they planned to implement in 2008.

This list focused largely on increasing program quality and efficiency,

including more job- and life-skills training, online registration, and a

call for greater involvement from the private sector. Later that year,

between July 2007 and the end of the fiscal year, DOES crafted a FY2008

performance plan that set several additional objectives for 2008.

Specifically, their performance plan called for DOES to “increase the

size, duration, and quality of the Summer Youth Employment Program.” The

plan set specific benchmarks of expansion: from 12,629 participants in

2007 to 15,000 participants in 2008 and from a 6-week program to a 10-week

program. To lessen funding pressures, the agency would attempt to secure

more private sector funding. Other

ideas were developed and incorporated into the agency’s planning process

well into 2008. Of all the proposed program improvements for 2008, there

were four that proved critical to the story of how and why events unfolded

as they did. The goals, some proposed by DOES and others by the Mayor and

City Administrator, were to:

1.

Dramatically increase enrollment, so that no young person

needing a summer job or experience would be turned away, no matter when

they registered;

2.

Expand the variety of opportunities, and thus the number of

work sites managed by the program;

3.

Change the payment method from an electronic benefit

transfer (EBT) system to a debit card system, which would allow young

people in the summer program to have quicker access to their money and not

be forced to pay ATM and other bank fees, as they had with the prior

system;

4.

Implement electronic time and attendance, intended to

improve the accuracy of payments and create organizational efficiencies by

eliminating paper records and manual entry.

FINANCES AND BUDGETING

Effective financial planning

for the Summer Youth Program requires accurately forecasting five

variables: 1) the number of young people who register for work; 2) the

ages of these participants (since the maximum hours one is permitted to

work per week varies by age); 3) the hourly pay rate; 4) the length of the

program; and 4) attrition, or the rate at which youth leave the program

voluntarily prior to its official conclusion.

The approved FY2008 budget

contained $24.5 million in funding for Youth Programs at DOES. This sum

includes funding for both DOES’s summer employment, indirect

administrative costs, as well as several other youth-oriented programs,

including the agency’s year-round program as well as agency

indirect/overhead costs for program management. Of this, approximately

$14.5 million was proposed and approved for SYP salaries and contracting

costs.

The sequence and timing of

the budget cycle is essential in explaining subsequent events. The Mayor

submitted his FY2008 budget request on March 23, 2007, prior to when DOES

committed to many major policy goals listed previously. The proposed and

approved budget assumed a 6-week program employing about 11,000 young

people. On May 15, 2007, Council approved the city’s FY2008 budget. Ten

days later, on May 25, President Bush signed into law legislation

increasing the federal minimum wage, which is the basis for the

program’s pay rate. Later in the year, DOES increased their employment

goals to 15,000 young people. The financial impact of these two decisions

led to a supplemental funding request approved by Council on December 18,

2007, that increased by $7 million the approved budget of DOES’s Youth

Program, and increased by $14.5 million the agency’s overall budget.

By the time the program

began in June 2008, funding attributed to the SYP increased from $14.5

million to $21 million. Nevertheless, the increases continued, as the

program’s budget was sufficient for only 15,000 participants. The third

of four budget increases occurred when the Mayor requested a

reprogramming, which Council approved on July 17, 2008, in the amount of

$10.8 million, bringing the SYP program funding to $32.3 million. The

administration attributed this increase to the unanticipated effectiveness

of recruitment and outreach, which resulted in more than 21,000

registrants, higher than the original or revised estimates for the

program.

The most recent and largest

budget increase was requested just two weeks later, in the amount of $20.1

million. This request, which would bring the budget up to $52 million, is

equivalent to the amount required to pay for all the young people who

signed up for the program as if there was perfect attendance. In other

words, this assumed that all the young people who were assigned to a

worksite would be paid for working the maximum allowable hours for the

entire duration of the program. The failures that led to the use of this

assumption in payment and budgeting is the central focus of this report.

REGISTRATION

The effectiveness of

outreach efforts to register young people for the SYP was unprecedented in

the recent history of the program. In 2003, the program employed 5,500; by

2007, enrollment exceeded 12,000. At a CapStat session prior to the 2007

SYP, the Mayor gave direction to DOES to improve their marketing efforts

to reach youth who would not normally enroll in the program. Formal

recruiting began as early as November 2007, when staff from DOES engaged

in outreach and interviewing of college students as they returned to DC

for holiday breaks. It continued throughout the winter and spring, as

staff made efforts to attend community meetings and find other means of

outreach and recruitment.

The effectiveness of

outreach efforts to register young people for the SYP was unprecedented in

the recent history of the program. In 2003, the program employed 5,500; by

2007, enrollment exceeded 12,000. At a CapStat session prior to the 2007

SYP, the Mayor gave direction to DOES to improve their marketing efforts

to reach youth who would not normally enroll in the program. Formal

recruiting began as early as November 2007, when staff from DOES engaged

in outreach and interviewing of college students as they returned to DC

for holiday breaks. It continued throughout the winter and spring, as

staff made efforts to attend community meetings and find other means of

outreach and recruitment.

Predicting the final number

of youth enrolled became a challenge, since the impact of the intensified

outreach efforts was not entirely known and there was no cut-off date for

registration. Staff expected a large number of last-minute enrollees, but

did not foresee how large that group would be. In March and April, DOES

believed that demand among youth people for summer employment would exceed

even the revised targets of 15,000. Because of an aggressive spring

recruitment campaign, DOES estimated that a large number of youth in need

of employment would likely not turn their attention to seeking it out

until the school year wound down. To accommodate this interest, the Mayor

gave direction for DOES to allow any young person who could demonstrate DC

residence to enroll in the program, without artificial registration

deadlines. As late as early

June, DOES senior staff believed that the program’s final registration

would plateau at between 16,000 and 17,000 youth, but they could not be

sure how significant a last-minute surge in registration would be.

Finally, in the second week

of June, the decision was made to include into the Summer Youth Program

summer school students at DCPS who were engaged in educational enrichment.

Youth were not paid to attend school. Rather, they were placed under the

supervision of a program coordinator after the completion of their

classroom work each day, and given work and enrichment assignments that

complemented their academic requirements. The rationale behind this

decision was to eliminate the incentive for a young person to leave summer

school in order to take a paid position in the SYP. By August, DCPS will

have doubled (to 443) the number of students who graduated from their

grade during the summer. The integration of these programs increased

enrollment by an additional 2,300 students.

Both the timing and size of

program registration combined to overwhelm program administration and was

a significant factor that led to disarray later in the program. The

dramatic expansion in the jobs program – nearly doubling it in size in a

single year – proved beyond the organization’s capacity to accommodate

and also execute the program’s core operations.

CONTRACTING AND NOTIFICATION

On March 3, 2008, DOES put

out a solicitation for project proposals from potential summer youth host

organizations. At the time,

the solicitation closing date was April 3, which would have provided ample

time to enter into contracts with the winning responses. In fact, DOES

maintained detailed contracting target deadlines when it began process.

DOES and OCP managers met prior to the solicitation to review language for

compliance with contracting regulations. According to interviews with an

OCP staff member involved in the project, the city received more than 30

proposals in response to the solicitation. The OCP project manager at the

time believed that more time was needed to answer questions raised by

prospective hosts. He then extended the closing date to April 23. Less

than a week after the closing date, the OCP manager assigned to the

contracts retired from government service.

Next came the negotiations

period. During this time,

contracting officials called organizations whose proposals were in the

“competitive range” to discuss possible proposal edits and revisions.

OCP then told the organizations that their “best and final”

proposals were due May 8. Three days prior to this date, a second OCP

employee assigned to the project left, in this case for medical leave. At

the time, she believed that the schedule was consistent with prior years

and on target for completion.

DOES evaluated the submitted

proposals and on May 21 sent a report on the proposal evaluations to OCP.

The following day the contracting office sent back questions about

the report to DOES, and evaluations were re-conducted May 23 – 26.

Contracts were drafted on May 29.

Just prior to finalizing

contracts, however, the OCP manager who was now assigned to the project

believed that errors and inconsistencies existed in the original

solicitation, despite the fact that it had been previously approved.

Since putting out another request would take too much time, OCP

decided to amend the existing solicitation and on May 30, with just over

two weeks left before the program began, discussions were reopened to all

organizations with proposals in the “competitive range.”

This round of discussions

closed on June 2, the “best and final” proposals from these

negotiations were due June 3, and the evaluation of these proposals was

conducted on June 4. By

contrast, the RFP closure date in 2007 was April 20. On June 5, OCP sent

contracts to the organizations with the highest-scored proposals for their

signatures. The number of

contracts sent out on June 5 was based on the amount of money budgeted for

the summer youth host organizations at that time.

On June 6 DOES told OCP that additional funding had been identified

and on June 9 contracts were sent out to additional organizations.

OCP received the first signed contract on June 10, and all 36

contracts had been signed by June 16.

The late completion of

contracts was a critical event. There were 36 contracts identified during

research, totaling more than $10 million and enrolling approximately 6,800

youth, which were finalized between June 10 and June 16. In fact, 8

contracts were awarded on June 16, the first day of the program.

Furthermore, these awards were all made on a contingency basis, meaning

that actual Purchase Orders were not established until a few days later.

Several purchase orders, consequently, were not approved until after the

program started. From DOES’s standpoint, despite a plea by its senior

executives, the process did not move quickly enough.

What makes the contracting

process so significant is that DOES’s ability to assign registrants to

worksites is fundamentally dependent upon it. DOES could only assign youth

to work sites when valid contracts existed with the work site host. If a

large portion of its contracted capacity was tied up in the procurement

process, then a large number of registered youth would remain unassigned

to job sites.

One week prior to the start

of the summer program, approximately 12,000 registered youth had not been

told where to report to work. DOES had prepared form letters to be mailed

out during that week to notify these youth of their assigned location, as

they had been doing previously. As contracts were awarded, kids would be

notified of their placement. For reasons still not known, only about 7,000

letters were actually sent out. Although the Director had been told that

“letters had gone out,” she was not told how many, or more importantly

how many were not, sent out.

Even if all letters had been

sent, there would still be several thousand youth who would be assigned so

late in the process that mailing was not a realistic option. In a last

attempt to reach all the youth still unaware of their assignment, DOES

placed a “robo-call” to inform the young persons and their families of

a website that DOES established where they could find out their work

assignment. Even if this attempt had proven successful, disarray would

have emerged at the start of the program since there were still several

host organizations with unapproved contracts entering the weekend and

there is a clear differential in access to the internet throughout the

city. In short, as the program began, youth did not know where to go to

work, and DOES did not know where to send them.

THE TIME AND ATTENDANCE SYSTEM

Prior to 2008, DOES

maintained a general purpose time and attendance IT system called the

Virtual One Stop. The system worked as follows. During the pay period,

site managers (those supervising youth at their jobs) would record time

and attendance on paper. At the end of each pay period all sites would

submit these paper timesheets to DOES’s Office of Youth Program payroll

office. Worksites sent timesheets to DOES in one of two ways. Hosts either

faxed them into DOES from the site, or the worksite would send the

original timesheets via a courier service arranged by DOES.

The “payroll office” within the Summer Youth Program consisted

of one full-time DOES employee who managed a team of summer youth, to whom

DOES gave the responsibility for entering time for the thousands of fellow

summer youth employees as the basis of their pay.

A manual, remotely collected

time entry system had obvious flaws. It required manual-entry timesheets,

timesheets of varying clarity, required a manual transfer of the document

via fax and courier, and then relied on summer youth to enter time

accurately for a workforce that was roughly one-third the size of the

entire DC government. There were ample possibilities for data errors and

inadequate auditing controls. To alleviate these risks, DOES’s IT Office

set out to replace it with a web-based time and attendance system that

would allow supervisors to enter data electronically at their worksite.

The system would then compile this information in a way that it could be

sent directly to financial institutions as the basis for payment.

What began as a sound policy

decision fell victim to poorly managed execution. DOES designed and began

development of a new time system without sufficiently informing or seeking

guidance from OCTO, the city’s central IT office. This lack of

communication, in hindsight, cut off expertise and resources that would

have ensured the quality of the program and sped up its completion.

The DOES IT office completed

the new application just 2 weeks prior to the start of the SYP. With so

little time for implementation, testing for errors and other bugs was

minimal. Minimal to no testing was provided by OCTO, since they were not

involved in the system’s development until after the program began. Of

equal importance, there was almost no time for training and genuine buy-in

among both DOES’s staff and host organizations. With less than two weeks

left before the SYP began, the DOES Director discussed options on how to

migrate over to the new system with her senior staff and the Office of

Youth Programs. The Director was concerned about the mounting work

required to accommodate the increasing flow of new registrants and host

organizations into the program. The Director pushed off system

implementation for another few days, until after the weekend of June 7 and

8, so that staff could continue enrolling youth into the old system, with

which they were familiar and therefore could more efficiently use.

On Monday, June 9 and

Tuesday, June 10, a week prior to the beginning of summer, DOES’s Youth

Programs Staff were trained on how to use the new time and attendance

application. Training the staff at host organizations and work sites to

use the new system proved more problematic on such short notice. DOES

rolled out daily webinars to train host organizations on the new system.

This was also problematic. The likelihood that these webinars would

actually reach everyone who needed to learn the system was small. Second,

an undermined but sizeable number of sites were not equipped with the

technology to accommodate web-based time entry, and the short notice left

virtually no time for upgrades. Knowing this, DOES maintained their

paper-based system, which would run identically to the old method,

allowing work sites to send in paper attendance forms to be entered into

the new time and attendance application at DOES’s central office.

Inadequate testing and data

verification in this new time entry system proved to be even more damaging

than the lack of training. Based on interviews with DOES managers, it

appears that a significant amount of outdated information was transferred

from the Virtual One Stop system to the new time and attendance

application. For example, some youth registered but were not assigned to a

work site. Youth and work sites from prior years would also show up as

active in 2008. In tests run by OCTO after the program went into crisis,

however, they concluded the system overall was sound. It is still unclear

if reported problems tied back to system design or how the staff used it.

Regardless of this, there was no time to diagnose these issues and make

adjustments prior to the beginning of the program.

THURSDAY JUNE 12: PERCEPTION VERSUS REALITY

On Thursday June 12, 2008,

the Mayor convened a CapStat session to receive a final briefing on the

SYP before the program’s start. CapStat is an accountability program for

reviewing agency performance and providing the Mayor and City

Administrator with accurate data about how effectively programs are

implementing major policies and carrying out their core operations. In

one-hour accountability sessions, the Mayor and City Administrator bring

into one room all executives responsible for improving performance on a

single issue, examine performance data around that issue, and explore ways

to improve government services, as well as make commitments for follow-up

actions.

The session scheduled for

June 12, entitled Summer Readiness,

looked at the status of preparations at four different agencies:

the Department of Parks and Recreation, DOES, DCPS, and OCTO.

In preparation for sessions, the CapStat team provides all

participants with statistics and graphs that highlight performance trends.

The charts for DOES focused on registration, funding, and placement.

At no point in the session

did the severity of the problems emerge.

The DOES portion of the discussion went smoothly.

When the DOES director said job sites would enter students’ time

online, for instance, no questions were asked about job sites’ capacity

to do this or what would happen if the online system failed.

The Director did mention that DOES had plenty of time – a

weekend, Monday, and part of Tuesday – to correct any payroll errors

after the first work week, but did not discuss a plan for mobilizing

employees if any major payroll glitch occurred.

Job placements were not discussed at all.

At one point the City Administrator asked about capacity versus

enrollment, but it was treated as an aside and the discussion quickly

turned to the OneCard.

In part because of the major

increase in enrollment, what DOES conveyed to the Mayor and City

Administrator was a program on the verge of success. More scrutiny should

have been given to DOES by the CapStat team to verify information and

provide enough skeptical pushback to ensure that the Mayor and City

Administrator received an honest appraisal. In retrospect, DOES built a

bigger program on an existing foundation – last year’s successful

program and expansion –which was subsequently found to have reached its

capacity for growth without significant organizational change.

By contrast, the CapStat

team and city executives provided far more scrutiny to the Department of

Parks and Recreation for the same session. The duration of questioning

directed at the DPR Director was nearly twice as long as that given to

DOES. The CapStat team requested direct data extracts of registration

figures for programs, conducted mystery shopping to see if waiting lists

existed for programs, and even sent a representative out unannounced to

outdoor pools to verify the number of life guards present and their names.

Consequently, the toughest discussion of the session centered not on DOES,

but on DPR.

Apparently, DOES leadership

had not pursued a deeper analysis of program structure, performance, and

readiness beyond that offered at the CapStat. This management presumption,

of trusting but not verifying, proved inadequate. The DOES director

reported meeting with her SYP staff every day for 30 days prior to the

program’s start, but took at face value information that her staff

presented. There was even a detailed project plan, replete with deadlines,

milestones, and project phases, loaded into Microsoft Project that planned

nearly every detail of the operation.

Most of the basic facts

surrounding the planning process, which have been described in this

report, were known by the Director. To roll out the program without

crisis, given the information available at the time, would have required

DOES to implement every aspect of its operation flawlessly, demonstrate

extraordinary adaptability, and have many external variables fall into

place. As major problems overwhelmed the program, DOES did not seek the

help it needed. This collective trust in the best-case scenario was in

stark contrast to the events that were about to unfold.

FRIDAY JUNE 13: CHAOS AWAITS

In reality, disarray was

unavoidable by Friday, June 13, the day before the beginning of

orientation and the last business day before the program began. The

individual planning processes described previously collided in a way that

compounded the damage of each by itself. DOES had 17,244 registrants on

record, but by mid-July would have 21,073. DOES

had planned for 14,341 placements and budgeted for 15,000, reflecting an

initial attrition rate of 15%. In fact, the program would place more

than19,000, an initial attrition rate of only 9%. The rush of interest

among young people looking for opportunities then needed to be connected

to a relatively untested time and attendance system that was entirely new

to its users. As planned, every young person was supposed to know their

assigned job placement and location of work before summer began, but due

to late contracts and last-minute enrollments, there were an unknown

number of youth – though certainly in the thousands – who on June 13

had no idea where they should report for duty the following Monday. Over

the next few days, thousands of young people would converge on DOES’s

headquarters on H Street, NE seeking assistance.

JUNE 14 – JUNE 20: THE FIRST WEEK

On Saturday June 14, the

DOES Director went to her H Street offices to pick up materials to bring

to the Convention Center where orientation was about to take place. She

was greeted with the sight of perhaps as many as 1,000 youth lined up

outside DOES’s doors. The young people that came to DOES that Saturday,

then continued to return for the next several days, consisted of those who

were interested in registering for a job, others who had registered

previously but did not know their site assignment, and a few whose

assigned work assignment was nonexistent.

An atmosphere of chaos,

tension, and eventually exhaustion persisted throughout the first several

days, according to those who worked the site. Another theme that emerged

during interviews was a lack of clarity about how to handle the large

numbers. Planned workflows were disregarded, in many cases because they

were neither designed for nor capable of handling the demands of those

first few days. The operation dealt with the problems before it, with

little focus on cause. One worker at H Street captured her observations:

On Monday, June 16, I became

involved in directly working with the youth.

I would receive youth who were: registering, getting work

assignments, and transferring assignments.

There was a line around the building, people had been coming in

through the weekend. There were kids moving all around the first floor.

Once I received an account I

was able to do all the activities. There

were several issues with the IT system, things as basic as scrolling

through work sites. In some

instances I was unable to de-couple a youth from a site to transfer to

another site. I would usually

persevere and get it done, which usually required unlocking by IT; however

I could hear people saying they couldn’t do it, so they would handwrite

a job site for the youth and send them out.

Youth with new job assignments had to

take a letter from DOES that identified them as the summer youth

assigned to the work site. The

printers were malfunctioning, perhaps due to being overworked, so I

witnessed a number of youth being told to write down where they were

supposed to go to and just show up there the next day.Many of the youth had not received

communication from DOES assigning them to a day/time to appear at the

convention center for OneCard and Debit card pick-up.

We were told to write down their names and phone numbers and tell

them that DOES would call and let them know when to show up. I did not

get the sense that someone from DOES was in fact collecting that

information.

Managers were also worried

that they might not have enough worksites to handle the unprecedented

demand for jobs. Just as much a focus of the team was finding or

confirming additional placements at worksites. The vast majority of these

new placements were filled successfully. But, workers did report youth who

were turned away from a site because of overcrowding, were sent to closed

sites, and in a few cases returned multiple times until they found a job.

Some employers adapted to an

unexpected increase in their youth workforce better than others. In some

cases, particularly placements inside District government, the increase

was dramatic. Logistical challenges around finding space and equipment

were common for these agencies, as was the task of creating additional

projects for their summer youth. No program-wide analysis has been

conducted on the extent to which the quality of the experience was diluted

as a result. Anecdotally, though, agency responses varied. It should be

noted that some host organizations felt that the sudden expansion was, in

fact, not a challenge; they had projects that could increase in size

easily. For others, there were difficulties identifying quality work

assignments.

Each evening, beginning on

Saturday and continuing virtually nonstop for the subsequent weeks, a team

of mostly DOES staff would work well into the night and early morning

trying to collect and process the information and forms collected during

the day. Among the registration forms were some that were dated back to

March, April, and May, but for some reason were never entered into the

system, or were initially collected by a third party and not brought to

DOES until mid-June. In other cases, DOES had young people who had

registered, had proof of registration, but were not in the system and were

not referred to a job site. It is unclear if these observations reflected

a broken IT system or an organization that had failed to enter the

registrations that they were given.

On Monday, June 16, and each

day throughout that work week, hundreds of young people continued to come

to H Street for registration and to the Convention Center for orientation.

At orientation, each young person would receive basic workplace training,

financial training, receive a OneCard for identification, and a debit card

for payment. Training occurred in four-hour segments of several hundred

youth per segment to cycle through all registrants. Only the debit cards

for those kids scheduled to attend a particular orientation were available

for dispersal. At the time, this policy was intended to maintain controls

over the deployment of debit cards. But amid the confusion, many youth

went to the wrong orientation session, or none at all. These youth started

their job without a payment mechanism in hand.

At this point, staff from

the Executive Office of the Mayor and Office of the City Administrator

became directly involved in operations, trying to alleviate the workload,

whether to provide management support, data analysis, or simply provide

additional bodies to staff intake stations. The involvement of the OCA and

EOM remains with the program to this day, and in the past two weeks has

assumed an increasing degree of control.

The primary focus of those

working at H Street was to move as many kids as possible through the

building. Amid the disarray and need to work efficiently, standard

procedures were replaced by ad hoc ones, which might have varied from

person to person. Electronic data capture was replaced with handwritten

notes, not always recorded on proper forms, but in some cases written on

any sheet of paper that was available. There is little evidence to suggest

that these lists were ever compiled and less to suggest that any analysis

of trends, root causes, problem sites, or recurring issues were identified

from this data.

Basic standards and controls

to guard against abuse broke down. Several workers – some DOES and

others pulled from other organizations – recorded and handled all the

information needed to register, including addresses and social security

numbers. This information, in many cases written on loose pieces of paper,

was needed to process the youth. Again, the pressure to cycle through a

large numbers in a short timeframe overwhelmed many concerns that would

normally halt an operation. One worker described the work process from her

experience:

Groups of youth were brought in a room for registration and

job referrals. They were given cut-up pieces of paper to write their

name and the last four digits of their Social Security number. These

papers were given to us, to search the system for their record. In some

cases, they would write their entire Social Security numbers down. If we

found the person in the system, we would print out or write out their

referral and their orientation schedule. If the person claimed to have

registered but we could not locate him or her in the system, then the

individual was asked to come to one of our work stations, sit down, and

write or verbally state their full Social Security number, address, and

contract information. This information was entered into the IT system. I

ripped up and threw out my paperwork. I saw papers with similar

information scattered around other work desks. I have no idea if these

papers were collected or not.

By every measure, however,

the most damaging consequence of the chaos surrounding those first few

days was that in the rush to assign kids to worksites, no one captured

accurately all the work assignments that were made. In short, DOES did not

know who worked where all of its summer workers were. Without this

information, the city could not accurately capture time and attendance and

thus could not accurately pay its summer youth workers.

CHASING PAYDAY: THE FIRST PAY PERIOD

The end of the first week of

work also represented the end of the first pay period. It was clear to all

the senior staff involved that after the events of the first week,

processing complete and accurate time and attendance data would be

impossible. Work sites could only enter time for youth they were

officially assigned. With so many unrecorded assignments and so many

worksites unprepared to use the new time entry system, it was not possible

to have a high degree of confidence in the data that was entered.

This left the administration

with an unwelcome choice: either it could pay according to official time

and attendance records, which would have inevitably underpaid or not paid

thousands of youth who legitimately worked during that first week, or it

could pay everyone registered in the system as if they had worked the

maximum hours, which would have certainly paid some youth for more hours

than they actually worked, since it is unlikely that every youth went to

work every day. This latter option would assume perfect attendance,

account for different age-based weekly hour limits, and given the

circumstances was seen as the only option that would ensure that all those

who did work received a paycheck. The administration chose to pay all the

kids. In explaining the rationale behind this decision, one interviewee

summarized it this way: “We did not want to punish kids for mistakes

made by adults.”

Even this, according to

interviews, did not prevent complaints of underpayment on pay day, in part

because DOES had not yet distributed a large number of debit cards (there

were 11,966 cards activated, and an additional 9,283 cards issued but not

distributed1). DOES set up a pay-day

processing center at the Convention Center to handle claims of incorrect

payment. Working with the OCFO, the city had on-site about 9,300

undistributed debit cards, as well as a stack of checks with amounts

filled in but blank name lines, along with CFO staff certified to process

payments (164 checks were actually used). Youth who had not received a

debit card would leave with one in hand. Those who lost their debit card

would have their original one cleared of any balance, have another

reordered, and because this process took 72 hours, would leave with a

check in hand.

THE SECOND PAY PERIOD

If mistakes were corrected

at that point, then the budget would not have ballooned to the extent it

did, because historically attrition does not become a significant factor

until later in the summer. The second pay period, however, led to the same

result as the first. In contrast with the first pay period, however, the

initial intention was to pay according to data reflected in the time and

attendance system. But many registered participants and many records were

still missing from the payroll system.

DOES also did not set up a

processing center after the second pay period, believing the data to be

relatively clean. When pay day hit, kids showed up at DOES’s H Street

headquarters with claims of underpayment or non-payment, claims that DOES

considered likely to be true. There was, however, no way to verify each

and every claim since DOES still did not trust data in the time entry

system. Left with the same choice as before – to err on the side of

underpayment or overpayment – the administration chose once again to pay

all kids for the maximum allowable hours.

Why did data integrity

issues persist weeks after they occurred? Why did the payroll problems

continue? Based on discussions with managers and other staff, two reasons

emerged: 1) everyone involved, but most notably DOES, consistently

underestimated the extent and complexity of the problem, and 2) DOES did

not demonstrate the organizational competence to methodically plan and

execute an appropriate response to these challenges. As a result, too few

people, and in many cases people with the wrong skill sets, were deployed

to resolve the crisis. Help was requested and given, but not enough help,

and more importantly, not the right kind of help. Everyone’s energy was

on reacting to the crisis immediately in front of them, rather than

solving the core problems.

In conducting research,

several examples were presented that demonstrated this. One person

described how ideas were proposed about calling all worksites to verify

names in the time entry application, but were never followed through.

Another interviewee described how worksites were allowed to submit time

and attendance forms up until only a few hours before data needed to be

sent to financial institutions. This left too little time for identifying

and correcting problems. In yet another example of the workflow

challenges, an interviewee described the following scene at a payment

center:

There was one day after the second pay period

where we had 500 or 600 kids outside H Street claiming payroll issues.

Yet, we had only one person who can cut checks. We had only two people

loading value onto the debit card. There was no capacity to handle

everything. The response then became to immediately load the max amount

on the debit card, rather than call the worksite, just to move people

along. There was no crisis management or considerations of workflow

issues.

Allegations of poor work

execution also consistently emerged in interviews. Some allege that work

Youth Programs staff did not enter time entry forms that had been

submitted. Others allege that clear directions were not followed by

several staff members. Research was unable to verify whether and the

extent to which willful insubordination occurred, but it should be noted

that it was raised by several people. Others, who did not agree with

allegations of widespread noncompliance, describe a workforce that by the

second and third pay period was exhausted, and not up to fixing the crisis

without additional help or replacements.

THE THIRD PAY PERIOD: ASSESSING THE DAMAGE

Shortly before the end of

the third pay period, the City Administrator convened a meeting with

nearly all the key managers to create a plan to gauge the depth of

problems with payroll. Gathered around the table was staff from DOES, OCA,

EOM, OCTO, and the OCFO. Enough data was obtained from the first two pay

periods to indicate that the SYP still could not account for the

placements of all its workers.

The City Administrator laid out a plan that

would call on a manual field operation to obtain attendance information

from work sites that did not report any information via the time and

attendance system during pay period two. This approach would serve as a

gap analysis, to determine the difference between identifiable hours,

staffing, site quality found through field visits, compared with payroll

data collected electronically during the first two pay periods. The

project managers assigned to this task pulled staff resources from

throughout EOM, the OCA, and city agencies to deploy to the field. In all,

roughly 60 DC employees went to the field over a three-day period to

collect paper time records, and bring them back to a central processing

center. The processing center, which was now moved to the Wilson Building,

was staffed 16 hours per day to enter time as it returned from the field.

These efforts were not

designed to gain control of payroll, but rather help with that task later

on. An analysis of data showed enough entry errors and inconsistencies to

not gain the government’s trust. Once again the data complexity of

challenges around time and attendance proved too formidable. For the third

consecutive pay period, the city decided to pay all the kids the maximum

allowable hours.

THE FOURTH PAY PERIOD: GAINING

CONTROL

The fourth pay period ended

on August 1. This report has been written between the end of the fourth

pay period and the pay day for that pay period. It was during the fourth

pay period that the city finally began to gain control of attendance and

payroll information. Several other changes allowed for this. First,

management of the crisis became a team effort involving several parts of

government. DOES’s IT office

was brought under managerial control of OCTO, the city’s technology

office, and DOES’s IT Director was replaced. A new project manager was

assigned by OCTO to manage all aspects of the crisis, and a “war room”

was established at OCTO headquarters, and staffed by data mining and

project management experts. Additionally, EOM began to pull appropriate

staff from throughout District government to supplement, and in some cases

take over, core functions of DOES’s Youth Programs Office.

The strategy to gain control

has been one of incrementally verifying and correcting entire classes of

data error. More specifically, the team developed a comprehensive listing

of every way that payroll information could be incorrect, then validated

the likelihood of error based on testing against available data. This has

allowed them to identify what errors are likely to exist, the financial

impact of those errors, and then focus their attention on those that are

of the highest risk. As each type of error is accounted for and resolved,

the amount paid to youth can begin to reflect the real hours, pay rates,

and participants.

This process, as it

continues to progress, has been critical in verifying the existence and

extent of waste, fraud, and abuse.

SHORT TERM ACTIONS (1): REDUCE PAYROLL

Payroll for the fourth pay

period will, for the first time since the program began, pay less than the

maximum allowable hours. The approach taken to start fixing payroll for

the program’s remaining weeks is to: 1) identify and remove from the

system people who are not part of the program at this point, and 2) ensure

that payments reflect the program’s most fundamental parameters

involving pay rates, age limits, and allowable hours.

More specifically, the focus

is to:

1.

Tighten our level of confidence in payroll data by:

a.

Validating all major sources of error, the findings of which

were highlight in this report, and stop payments to individuals whom we

have a high degree of confidence are no longer in the program

b.

Implementing sanity checks on payrolls prior to look for

known issues that cause re-work at payday processing centers

c.

Eliminating the practice of maintaining information

off-line, and bring online all prior records

2.

Implement strong external communications with participants

and their parents by:

a.

Contacting all individuals impacted by changes to payment

strategy through multiple communications channels such as robo-calls, text

messages, use of an outbound call center, and others

b.

Establishing a call center that will allow for many payment

disagreements to be resolved without requiring that a participant travel

to a processing center

3.

Strengthen Pay Center readiness by:

a.

Opening pay centers in advance, which will result in problem

resolved in advance and shorter lines

This plan will scale back from the perfect attendance presumption in the

following ways:

SHORT TERM ACTIONS (2): IDENTIFY AND RESPOND TO WASTE, FRAUD, AND

ABUSE

The full extent of waste,

fraud, and abuse is not yet known, but significant progress has been made

in gauging the likelihood and extent of it in the program. In some cases,

allegations of fraud and abuse have not borne out. But in many cases, some

presence of fraud has been verified. Collectively, there is great concern

that hundreds – and perhaps thousands – of individuals registered in

the youth program have been knowingly engaged in fraud.

To be thorough, the report

examines each known allegation separately. They are as follows:

- Is there

participation by non-District residents?

- Finding:

Verified but minimal presence in program, low financial exposure.

Out of more than 21,000 participants, only 207 were found to with

recorded addresses outside of the District. Of these, it is unclear

how many are considered under the care of the District (i.e., in

foster homes). This does not exclude the possibility that a young

person would show fraudulent proof of residence. - Action:

Given that due diligence was conducted upon registration, no

immediate action will be taken to fully address this allegation

until more significant challenges are resolved. DOES will

incorporate lessons from this analysis into how it plans for 2009. - Are

participants working but still not officially registered? - Finding:

No longer present in program, low financial exposure. This would be

a source of underpayment of youth. At this point, however, the team

believes that after three pay periods, all errors of this kind have

been resolved through in-person processing and data clean-ups to

date. - Action:

DOES will incorporate lessons from this analysis into how it plans

for 2009. - Are individuals

not registered, not working, yet getting paid? - Finding:

Not yet validated, but a potential area of high financial exposure.

When the prior time entry system migrated to the new system,

outdated names were not entirely cleansed from the system. In all

more than 8,000 names were transferred from one system to the next.

Most of these names are valid. If some date back to prior years and

remain in the system this year, they would in fact be getting paid.

At the time of this report, the OCTO team was identifying how many

names came from the old system, and do not have any other sign of

active participation, such as signing up for a one card, having time

entered this year, etc. - Action:

Once names have been identified, the city will terminate payment to

them and remove their debit cards from the system, and identify for

further action if there are any individuals in this group who

activated their debits cards. DOES will incorporate lessons from

this analysis into how it plans for 2009. - Are individuals

getting are paid, yet are listed as working at sites whose programs

have ended or sites have otherwise closed? - Finding:

Not present in the program at this point, potentially moderate

financial exposure. The earliest site closings are August 1, which

would impact the fifth pay period. - Action:

OCTO is currently validating site closures, and will be able to

remove youth assigned to these programs from the payroll system,

unless they appear to have joined a new program or worksite. DOES

will incorporate lessons from this analysis into how it plans for

2009. - Are individuals

who began the program, but were terminated by their employer, still

being paid? - Finding:

Verified but minimal presence in the program, low financial

exposure. To date, 122 out of more than 21,000 youth have been

dismissed by their employer. However, to date they have been paid

along with other youth. - Action:

Immediately remove these individuals form payroll records. DOES will

incorporate lessons from this analysis into how it plans for 2009. - Are individuals

working but have not been paid? - Finding:

Very low probability of existing in the program, moderate financial

exposure if it does. There are approximately 2,800 debit cards that

have not been picked up. Potentially, these could represent

unrealized earnings by program participants. - Action:

OCTO is currently examining if the city has any record of an

interaction that would suggest that the individuals associated with

these cards are or have been participating in the program. If they

are none, then this funding can be reclaimed by the city.

DOES will incorporate lessons from this analysis into how it

plans for 2009. - Are individuals

who have since dropped out of the program are still being paid? - Finding:

Validated as existing in the program, moderate financial exposure.

There are 1,881 individuals who have displayed perfect absenteeism

for an entire pay period, but are registered in the system and have

some type of interaction – perhaps they worked previous pay

periods – that demonstrate a legitimate reason for their presence

in the system. - Action:

These individuals will be removed from the payroll system. DOES will

incorporate lessons from this analysis into how it plans for 2009. - Are individuals

older or younger than the allowable age range for the program working

and getting paid? - Finding:

Verified but minimal presence in the program, low financial

exposure. There have been 104 individuals who based on Social

Security records are either older than 21 or younger than 14. The

vast majority of these individuals are older, not younger. - Action:

Terminate immediately and remove from payroll.

Pay for work completed by those who are 13 years of age. DOES

will incorporate lessons from this analysis into how it plans for

2009. - Are individuals

being been paid twice, once by their private employer and once by the

city? - Finding:

Highly likely to be present in the program, but with minimal

financial impact. The city has received complaints from parents with

children who were placed at private employers, and paid by those

employers, but also have had city-funded accounts (debit cards)

created in their names (essentially reporting unearned money). It is

highly likely, given the decision to pay all children the full

amount, that these youth received two payments, though many may not

have activated their debit cards. - Action:

The city will cross reference payroll names with those assigned to

unsubsidized private employers, and remove them from payroll. DOES

will incorporate lessons from this analysis into how it plans for

2009. - Are individuals

paid the wrong pay rate? - Finding:

Not yet verified but likely present in the program, moderate

financial exposure. During the prior pay periods, the payroll system

adjusted pay rates to account for work sites that paid a wage higher

than the federal minimum. However, several work sites pay all

participants at a rate higher than the federal minimum wage. In

researching the basis for this, the data team has not yet found any

documentation approving this, either in contracts or other

materials. This is an area of great concern, and if confirmed, is an

example of negligence. - Action:

Continuing to verify if pay rates are contained somewhere in

contracts or other legally sufficient documents. - Are individuals

getting paid for more hours than they worked? - Finding:

Widespread, high financial exposure. By definition, when the city

chose to pay every registrant the maximum hours allowed, many young

people who worked only a portion of their scheduled hours were

overpaid. - Action:

This is the most significant and challenging problem to solve,

because it involves thousands of individual entries at hundreds of

worksites, for reasons previously described in this report. It will

likely require continued field operations to work with every host

and site to ensure accurate attendance is being captured.

SHORT TERM ACTIONS (3): THE CONTINGENCY RESERVE

By the time of the third

payroll, the program had exhausted its revised budget.

Under the local Anti-Deficiency Act only two options existed:

either an external source of funding had to be identified and made

immediately available to cover cost overruns; or the program had to

terminate immediately after only five weeks, ending summer employment for

thousands of District youth who had registered, worked, and planned to

continue to do so for the remainder of the summer.

Cost estimates for a worst-case scenario (in which there is no

improvement in the program’s operational problems, most importantly the

ability to verify time and attendance and thus deduct attrition from

payroll expenses) projected that the program could exceed its revised

budget by $20.1 million. On

July 30, the Mayor formally requested an allocation up to this amount from

the Contingency Reserve Fund, while efforts to reduce the cost of the

program continued.

The Contingency Reserve is a

critically important component of the District’s General Fund, created to

meet unforeseen needs that arise during the fiscal year, including revenue

shortfalls, unexpected obligations caused by changes in Federal law,

natural disasters, and other unanticipated events with budget

implications. As of December

31, 2007, the date of the most recent official certification, the

Contingency Reserve fund balance was $223.5 million, including a

receivable of $53.1 million. Any

allocation from the Contingency Reserve must be repaid within two years.

As noted in the Mayor’s July

30 letter, it may be possible to repay the Contingency Reserve from the

existing, certified fund balances of Special Purpose (O-type) accounts

managed by DOES. Two of these

accounts (0611 and 0624) were created to provide for the administrative

costs of managing other employment-related programs.

Because revenue collections have greatly outpaced recent spending,

the balances of these administrative accounts nearly tripled from $7.7

million in FY 2004 to $21.4 million at the end of FY 2007.

In addition, the balance of an account (0612) created to hold UI

interest and penalties grew fivefold, from just under $208,000 in 2004 to

nearly $1.1 million in FY 2007. A

fourth account (0614/0600), with a balance of $1.4 million, has been

dormant (with no revenues or expenditures) since FY 2005.

While the balances in these accounts appear to be sufficient to

repay the Contingency Reserve allocation to DOES, doing so would require a

legislative change to the respective statutes that created the accounts.

Given the administrative missteps that have caused the cost overruns in

the summer youth program, it may be appropriate to repay the Contingency

Reserve from these DOES administrative accounts.

WHAT WORKED

Program successes are not

this report’s focus, but also should not be lost or forgotten. In fact,

they need to be recognized as a fundamental to next year’s planning. In

the course of researching problems, several innovations and improvements

show demonstrable progress. Among those are:

o

A significant increase in the number of hard-to-reach youth

were provided a summer job than in prior years. This factor contributed to

the managerial challenges, but in itself should not be dismissed as

without value.

o

DCPS more than doubled the number of summer school students

who graduated due to their summer studies, which they attribute largely to

not losing summer students to non-academic jobs

o

Juvenile arrests for violent crimes 2008 are down 34% (148

in 2007, 98 in 2008), while arrests of adults for violent crimes are up 4%

(599 in 2007, 620 in 2008). Juveniles arrested for stolen vehicles are

down 60% from 2007 (73 in 2007, 29 in 2008), while adult arrests for that

crime are down 20%.

o

Introduction of the debit card system that allows

participants to avoid bank fees and gain quicker access to their money.

o

Introduction of the One Card, a form of identification for

program participants that also contained a Metro SmarTrip chip, loaded

with $10, to make commuting to jobs easier.

o

Success of several large programs with defined objectives

and enrollment, such as the District Department of the Environment’s

Green Team. This program consistently retained a workforce of 250

individuals over all pay periods to date, who cleaned up neighborhoods

surrounding rec centers, while receiving job training in emerging “green

economy” industries, such as green roofs, tree maintenance, and water

quality monitoring.

o

A second effective program was run by the Department of

Youth Rehabilitative Services, which enrolled 260 youth. Youth enrolled in

gained knowledge and skills that they can reflect on their resume as well

as apply to future life experiences. Youth

participated in landscaping (on

grounds and within the community), where youth planted vegetables and

mowed lawns for elderly residents; arts

craft corps, where youth made murals and signs for the new facility;

media advocacy, where youth learned the art of photography; outdoor

leadership, where youth build boats and rope courses; and culinary,

where youth learned the art of cooking and food preparation.

Such activities not only gave youth an opportunity to give back to

the community, but enhanced their leadership, conflict resolution, and

communication skills.

LONG TERM ACTIONS: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR 2009

There are a number of

changes that the department should make for 2009, some of which are listed

in the prior section on allegations. But, several critical strategic

lessons stand out:

1.

Invest in what works,

stop funding what does not. This sounds obvious, but is often

overlooked. It was clear during research that some programs provided a

higher quality experience to young people than others; some programs can

demonstrate results and others do not. Yet, the number of organizations

that receive funding year-after-year suggests that host organizations are

not asked to demonstrate that they prepare young people for jobs later in

life.

2.

Maintain a commitment

to providing quality experiences to a large number of District youth.

It was not the findings of this report that aggressive recruitment goals

alone caused problems; rather, the more critical root cause was the

organization was unable to implement these goals effectively. Fraud and

abuse, while important to highlight and eliminate, was not the norm.

Rather, the youth that do not bother to look for summer work until

June may in fact be the very young people who the city should target and

build its operation around.

3.

Reassess leadership,

skills and people required to manage and run the organization, and put the

right people in the right job. The operational complexity of

maintaining a 20,000-person summer program offering quality jobs likely

requires different skills and knowledge than running a 12,000-person

program with an April registration deadline. It demands a commitment to

and comfort-level with a sophisticated amount of data management, project

tracking, quantifiable program evaluations and technology. A complete

reorganization and a top-down assessment of whether individual skills

match requirements should occur within the Office of Youth Programs.

4.

Enforce time entry

requirements at host organizations. Despite clear language in

contracts that require time tracking, no incentives exist or are utilized

to enforce these requirements. Host organizations not compliant with time

entry should be subject to penalties, and consideration for future

de-funding.

5.

Have job assignment

available for youth as they register, with goal of registering a higher

percent of participants before the program begins, by securing contracts

earlier or migrating to multi-year contracts with providers. The

delays that plagued the 2008 program cannot continue in 2009. Given that

the District knows that it will need host organizations every year,

multi-year contracts provide a vehicle to eliminate (except for

6.

Relentlessly

challenge assumptions, and train people how to respond to unexpectedly

large workflows. Clearly, assumptions for around the timing and

progress of preparations need to be thoroughly verified by data. It is not

enough to just discuss unexpected events. Contingency plans should be

developed. Staff should be trained with processes to adapt to

less-than-ideal scenarios, most notably how to build processes and

workflows to manage large volumes of in-person requests.

7.

Eliminate all paper

processes. Reliance on paper-based processes, even when online

alternatives were available, is a pervasive theme of this report. The

entire workflow, from registration and placement to time entry, needs to

be managed online.

8.

Continually validate

information to stop fraud and abuse before or just after it occurs.

The actions taken by OCTO during the fourth pay period proved that it is

possible to identify waste, fraud, and abuse quickly to eliminate it from

the program. This requires a relentless commitment to searching for data

“errors” as they appear in the system.

9.

Integrate the debit

card with the one card. Each program, individually, was effective in

2008. It remains inefficient, however, to require young people to register

for cards and maintain two separate cards. Given the presence of one’s

photo on the ID, it could also the city’s ability to guard against

abuse.

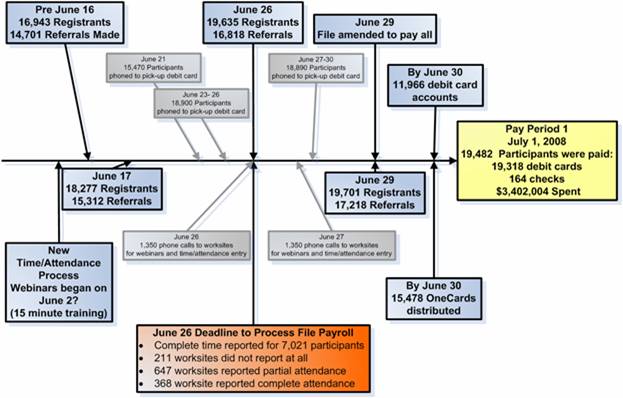

APPENDIX A: TIMELINE OF FIRST

3 PAY PERIODS

1. The data team working on the project is still

clarifying this precise numbers.